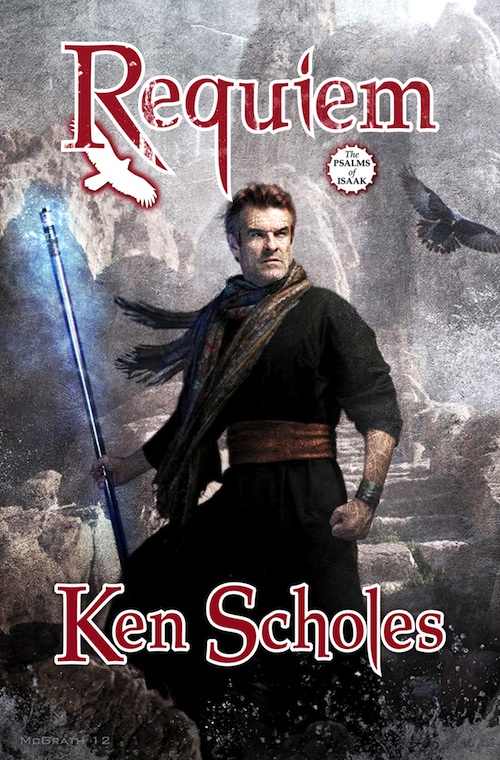

Check out Requiem by Ken Scholes, out on June 18:

Ken Scholes’s debut novel, Lamentation, was an event in fantasy. It was followed by Canticle and Antiphon. Now comes the fourth book in the series, Requiem.

Who is the Crimson Empress, and what does her conquest of the Named Lands really mean? Who holds the keys to the Moon Wizard’s Tower?

The plots within plots are expanding as the characters seek their way out of the maze of intrigue. The world is expanding as they discover lands beyond their previous carefully controlled knowledge. Hidden truths reveal even deeper truths, and nothing is as it seemed to be.

Prelude

A gibbous moon hung in the predawn sky, casting shades of blue and green over a blanket of snow. Fresh from the gloom of the woodlands behind her and not even an hour past the warmth of the thick quilts and crackling fire of her family’s home, Marta clutched her stolen sling and cursed the rabbit for running so far and so fast.

She’d not meant to be gone so long. She’d only meant to quickly and efficiently do her part, proving to her father and her brother that she could. Still, if she caught it, skinned and gutted it, she could have it in the stew pot before the sun rose.

Marta moved slowly, following the slight trail the rabbit left in the thick snow, her sling loaded and ready in her left hand.

“Everyone,” her father had said since her mother died, “must do their part.” She’d been selling fresh produce in Windwir two years ago, same as she’d always done, when the ground shook and the pillar of fire rose up into a Second Summer sky to choke out the sun.

Everything changed that day. And then kept changing.

First, there had been the armies. Then, eventually, the soldiers had retreated and the Marshers had come, though now they wore black uniforms and called themselves Machtvolk. Now they built schools and encouraged the children to attend, though Marta’s father had not permitted her to. At least twice a month, the black-robed evangelist visited their doorstep and entreated Galdus to send at least his daughter so that she might be properly educated.

Part of her resented that her father held her back, relegating her to do her part, namely sweeping and cleaning and tending the garden during the spring and summer. But another part of Marta reveled in being one of the few children who did not attend the Y’Zirite school.

Still, she heard things through her friends. She knew about the Crimson Empress and the Great Mother and the Child of Promise and how their advent meant the healing of the world. She had heard bits of scripture and had listened to the evangelists expounding upon it in the village square. She’d even seen the Great Mother not long ago, just after the earthquake, riding south in a small company, fast as fast can be on magicked horses. And she’d guessed that the bundle she carried close beneath her winter cloak was the Child of Promise, Jakob.

They’d lined the muddy road to catch a glimpse, though her father’s grim jawline told her that he did so with no sense of the faith or joy the surrounding villagers felt.

Everyone must do their part.

Marta pushed ahead and caught sight of movement near the tree line. Beyond it, she heard the quiet rush of water that marked one of the many creeks that ran into the Third River. She watched her breath gather in a cloud ahead of her face and measured the distance with her eyes. The rabbit was just out of reach.

Picking up her pace, she twirled the sling and listened to its buzzing as it built on the air.

She broke into a run as the rabbit moved into the trees, and gasping in frustration, she loosed the stone. It shot out and hummed across the clearing, cracking against a tree even as she fitted another into the sling’s pocket.

Overhead, the sky moved toward gray.

Then, something happened. There was movement—heavy movement— within the tree line and she heard the rabbit scream even as she heard the snap of breaking bones.

She felt a sudden rush of fear and tasted the copper of it in her mouth. But still, her feet carried her forward. She caught a glimpse of something in the trees moving with long, deliberate strides off toward the river. It was tall and looked like a man.

Marta glanced down, saw the speckle of blood on the ground and the large footprint. I should go back, she thought. I should tell my father there is someone in the woods.

But it would easier to go back with the rabbit in hand. And it would be more efficient to go back with some idea as to who hid in their woods.

It moved faster than a man and she jogged to keep up, staying well behind.

When it paused, she stopped in her tracks. And when it looked over its shoulder in her direction, she felt her mouth go dry.

Eyes that burned the color of blood opened and closed on her. “Do not follow me, little human,” a wheezy, fluid voice said.

She swallowed, then summoned up her own voice, trying hard to not let it shake. “Give me back my rabbit.”

It turned and moved off again. But now it slowed, and she drew closer.

It was a man made of metal, but no metal she’d ever seen before. It was a silver that reflected back their surroundings—the white of the snow, the blue-green of the moonlight, the charcoal shadows of the forest— and it moved with liquid grace, its joints whispering and clicking faintly as they bent.

“Who are you?”

They were near the river now and the cliffs it ran beside. The metal man paused, and she was close enough now to see tears in its red jeweled eyes. “I do not know who I am,” he said.

“Where are you from?”

The metal man looked up, its eyes taking in the moon. “I do not know.” It shuddered slightly as it spoke.

Marta took another step forward and the metal man spun suddenly, moving off in the direction of the cliff-side, the rabbit hanging loosely in one slender, silver hand. Again, she jogged to catch up.

She’d heard tales of mechanicals though she’d never seen one, and an idea crept to mind.

“Are you from Windwir?”

This time, its movements were violent, and she leaped back when it spun toward her. “I told you I do not know, little human. It is not safe for you to follow me.”

She gritted her teeth. “Then give me back my rabbit.”

He looked down at the rabbit and then looked at her. “The human body contains on average two congius of blood.” He leaned forward. “You are not fully grown, but you would suffice.”

She felt herself go pale. She even willed her feet to carry her backward, to fly her home to the warmth of her waiting house and bed. But they refused her. Instead, she stood transfixed by the creature that towered over her now, the sling dangling powerlessly from her hand. She wanted to ask him what she would suffice for, but couldn’t make her tongue work either.

When he turned away just as suddenly, she heard her breath release. Striding to the cliffside, he disappeared behind a boulder.

Shaking, she followed slowly this time.

When Marta reached the boulder, she saw that it hid a crack in the granite wall, and just within that crack, she saw the metal man crouching over a battered wooden pail. She winced as those bare metal hands ripped open the rabbit’s throat and upended it so that its blood could drip into the bucket.

I should be silent, she thought. I should flee now and get the others, tell them what hides here. But as she watched, she saw the metal shoulders begin to shake, and she saw silver tears roll down silver cheeks to mix with the rabbit’s blood.

“Why do you need blood?” the girl asked in a quiet voice, though she wasn’t certain she wanted to know.

The metal man looked up and raised a tattered brush in his other hand.

“To paint the violence of my dreams,” he said. And in the dim red light of his eyes, Marta saw the words and symbols that covered the walls of his cave and she gasped.

Outside, a cold wind picked up as the moon began its slow slide downward into the horizon and the sky went purple with morning.

Chapter

1

Rudolfo

Outside, a cold wind muttered along the edge of the Prairie Sea, whispering over the canvas of a hundred tents. Inside, Rudolfo waited for a meeting he could not bear to hold but could not avoid.

“They are nearly here, General,” said the Gypsy Scout at the entrance of his tent.

Rudolfo looked up from his work table. He’d reached his western border just three days earlier and had whiled away the days going through yet more reports and communications.

Much had happened since he’d left the north and their exploration of the Beneath Places. The magnitude of it all left his head aching.

First, there had been the earthquake. It was slight on the surface, but many of the tunnels far below them had collapsed. Tunnels that Rudolfo’s scouts and miners had been mapping. The tunnels that Isaak and Charles had taken to follow the other mechoservitors west.

Next, Aedric’s birds and runners had reached them with warnings about what they’d found in the Watcher’s cave, followed soon after by word that Winters was returning with an unknown number of Marsher refugees. And though he’d assumed Jin and Jakob and their entourage would return with them, he’d heard no word from any of them, and that perplexed him greatly. Still, he’d convinced himself it had to do with the difficulty they’d had with the birds of late.

Then, most recently, all communication out of Pylos had suddenly ceased, followed by a flurry of birds that bore dark tidings of a desolation larger even than that of Windwir.

An entire nation lost. Every man, woman and child. Gods, he thought. It couldn’t possibly be true. But Rudolfo knew in his bones that it was.

And now this. He looked up at the young lieutenant framed in the morning light. Nearly two thousand of his kin, his people, approached on foot, and he would have words with one of them. “When will they arrive?”

“Within the hour,” the scout answered.

Rudolfo nodded. “I will meet with Kember alone,” he said. “Bring him to the watchtower when he arrives.”

The officer inclined his head. “Yes, General.”

When he was alone again, Rudolfo turned to the plate his cook had left for him and scanned reports while picking at bits of chilled rabbit, pickled asparagus and rice. Between bites, he sipped cold, sweet chai and tried to imagine what he would say to the man who’d been a father to him since the first days of his orphanhood.

He waited until the last minute to dress, then slipped out of his tent to stride through frozen blades of grass and snowdrifts to the skeletal wood tower that stood watch over the Western Steppes. Around the tower, hasty structures and tents formed a small town with the first soldiers of his standing army taking up their posts to guard the closed borders of the Ninefold Forest, there at the edge of the Prairie Sea.

Rudolfo climbed the stairs, his Gypsy Scouts behind and before him as he went. He slipped through the heavy oak door and into a cold room furnished simply with a table and chairs. He sat and waited.

When the door opened, he looked up as his second captain ushered Kember in.

The forced winter march had not been kind to the old man, and it pleased Rudolfo to see it in the hollowness of his eyes and his weekslong growth of beard. Behind him, Philemus stood by silently.

Rudolfo did not invite the former steward of his Seventh Forest Manor to sit. Instead, he met his stare coolly.

“How long, Kember?”

The older man said nothing.

“Damnation,” Rudolfo roared, his fist coming down upon the table. “How long?”

“Fifty-three years,” Kember finally said.

More than a dozen years before Rudolfo’s birth. He didn’t want to believe it. “Show me the mark.”

Kember shook his head. “I was not permitted the mark. Most of us weren’t. It was your father’s—”

Rudolfo cut him off. “Did my father take the mark?”

Slowly, Kember nodded. “He did, Lord. And his fondest desire was that in time, you would, too.”

The Gypsy King felt rage twisting in his gut like a blade. “That won’t happen.” He leaned forward and let the rage settle into his voice, chilling his carefully chosen words. “But I will tell you what will happen,” Rudolfo said. “You have one opportunity for grace. Otherwise, the Physician Benoit will be here tomorrow morning to assist in your redemption.” Here, he nodded to his second captain. “Philemus will spend today and tonight with you, asking questions, and if he is satisfied with your answers, you and your people will leave and never return. Your properties will be forfeit and divided among the refugees your faith and treachery helped to create. The edicts are posted; this resurgence will not be tolerated in my forest.”

Rudolfo paused and studied the man’s face. It was too calm for his liking. “If Philemus is not satisfied with your answers, an appointment with my Physician will be arranged.” Still, that calm remained, and Rudolfo forced a smile to his lips. “An appointment,” he said slowly, “not for you but for Ilyna.”

The mention of the man’s wife was the first sign of his resolve slipping, and Rudolfo continued. “And for every answer you do not give with promptness, accuracy and sincerity, Benoit will cut a piece of her away. If necessary, you will be afforded the opportunity to watch and hear this redemptive work.”

The blood drained from Kember’s face. “I will answer your questions, Rudolfo. Certainly I will.” His voice caught, and it pleased the Gypsy King to see the man’s composure dissolve. “But hear this: what is coming is a work carefully conceived for your benefit and for the healing of the world. Your father would be ashamed of you for your actions today.”

“My father betrayed us all,” Rudolfo said, “and I am ashamed of him for his own actions.” And for the first time, he understood the sharpness of those feelings as that betrayal cut its own mark above his heart. He stood. “And I am ashamed of you, as well, Kember.”

He turned his back upon the old man, and left his second captain to the work of interrogation.

Reports of Philemus’s progress trickled in throughout the day, and Rudolfo tried to busy himself with work but found his taste for it had gone sour. He sat and stared into nothing, his hands still upon the pile of papers.

Finally, as afternoon became evening, he stood, put on his coat, and slipped out into the cold.

At first, he wandered the camp under the pretense of inspecting his men, but despite his best efforts, he felt his booted feet pulling him beyond their military outpost to the large cluster of mismatched tents that formed the exiles’ camp. His Gypsy Scouts, bolstered by two companies of his Wandering Army, stood somber watch over the ragged group of frostbitten Y’Zirites.

Rudolfo walked that perimeter, his eyes intentionally meeting those of the exiles. Most looked away beneath the hardness of their king’s angry glare. Some met his eyes with quiet resolve. Rudolfo was careful to keep his stare level, though he was not sure why he’d come here. It was not as if he would understand any better from the exercise or that if he did somehow gain knowledge, that it would change the course of action he’d committed to.

Their faith is a poison laced with sugar. He thought of his father and felt the grief again. A question arose within him that he’d asked many times these past two years. “Why?”

He heard footfalls behind him and turned to see Lieutenant Daryn— the gypsy scout from earlier—approaching. His face was grim.

“General,” he said, “the Marshers have reached the western watch.”

Rudolfo quickly calculated distance. They’d arrive within the next two hours. He felt relief building in him. Sending his wife and son into the enemy’s den after the explosion had been the best course of action at the time. But now, with his borders guarded and with the surgical knifework with which the conspiracy had been cut out of the Named Lands by Ria’s people, it was time to have them at home. In the midst of the madness his life had become, Jin Li Tam and Jakob were what anchored him.

“Excellent,” he said, and gave a tired smile.

But the smile faded at Daryn’s troubled face. The lieutenant looked away quickly; then he met Rudolfo’s eyes. “Charles and Winters are with them,” he said. “Lady Tam and Lord Jakob are not.” He paused. “Isaak and Aedric are also missing.”

Rudolfo felt it like a fist in his gut, and his knees went weak. “Where are they?” But before the man could answer, Rudolfo was racing toward camp and shouting for his fastest horse.

Winters

The moon was a smudge of blue and green behind a veil of clouds, and Winteria bat Mardic walked beneath it, forcing each step despite the protest of every muscle in her body.

It had been a long ten days, moving from village to village on foot. Exhaustion saturated her. She spent her days putting one foot in front of the other, moving among her people as they made their way southeast. And she spent her nights tossing and turning, struggling beneath the weight of bad tidings she knew she must soon share with Rudolfo about Jin and Jakob, about Isaak and Neb.

Neb. She’d been terrified of him. Something had changed the boy into . . . what? She didn’t know. But after healing her cuts with a touch, he’d gone out to face the Watcher, and he’d held his own against that ancient metal man in a battle that left a wide path of ruined forest behind them. And he had not come back. Neither had Isaak or the Watcher.

She glanced over her shoulder to where Charles sat upon the back of a tired pony. His face had paled at the earthquake, and he’d said fewer than three words to her in the days since. But she’d seen him wiping tears from his eyes from time to time, and she suspected strongly that he knew what she feared most—that Isaak was not coming back.

And Neb may not be either.

She shook the thought away, refusing it. She needed to believe that he somehow escaped. That somehow, he was doing what her people’s dream had called him to, seeking their Home, and she wanted to believe that maybe Isaak had escaped with him. And that maybe, somehow, they’d wrested the final dream from the Watcher before they fled.

But she saw no evidence of that, and she’d left with her people the morning after the earthquake, even while the Machtvolk scouts and soldiers scoured the forest for some sign of where Neb and the mechoservitors had vanished to.

Scout whistles ahead startled her and she stopped abruptly, hearing the sound of fluttering feathers grabbed from the air by catch nets. She knew they were close now, and soon Rudolfo would demand answers of her.

She sighed and steeled herself, adjusting the knives she wore at her hips before hurrying ahead.

She heard the pounding of hooves first, followed by a whispering wind that betrayed the approach of magicked scouts.

Winters reached the front of the caravan even as a dark mare and turbaned rider crested the rise of frozen scrub ahead of them. There was something different in his posture now, but it was unmistakably Rudolfo. His head moved from side to side, taking in the scattered line of refugees.

“Hail, Lord Rudolfo,” she shouted, stepping out in front of her people. The Gypsy Scout Aedric had left in charge materialized beside her. “I’ve brought more orphans for your collection.”

He didn’t answer. Instead, Rudolfo whistled the horse forward and toward them, letting the beast pick its footing carefully on the snowswept slope. As he drew closer, she saw his eyes narrow at the sight of her scars, his lips pursed in anger.

When he spoke, there was a cold edge in his voice that she was not accustomed to. She could feel the weight of his stare. “Where is my family?” Then, his eyes shifted to the Gypsy Scout. “And where is my first captain?”

She watched the man try to meet Rudolfo’s gaze and fail, hanging his head in wordless shame. “Perhaps we should discuss this matter in private, Lord,” she said.

He turned on her quickly, moving the horse in close. “Where,” he asked again, this time slowly, “is my family?”

She swallowed. “They have left the Named Lands,” she said, then glanced over her shoulder at the people who stood nearby. “It is a matter we should discuss privately, Lord Rudolfo.”

He looked away from her and to his scout. “And Aedric?”

The scout reached toward his sash. “I bear a letter from the captain addressed to you, General.”

Rudolfo raised his hand. “Enough,” he said. The rage Winters saw in his eyes startled her and she would have looked away, but he did first. He scanned the crowd. “Where’s Charles?”

“I’m here,” the old man said.

“What of Isaak?”

Winters turned in time to see Charles meet Rudolfo’s stare. “Lady Winteria is correct,” he said. “We should speak privately. These are sensitive matters.”

Rudolfo took a long, deep breath. He’s wrestling with his anger, she realized. “Very well,” he said. Then, he dismounted and handed the reins over to a scout who materialized at his arm. He looked first to Charles and then to Winters. “Walk with me. Both of you.”

They set out at a brisk pace, their breath frosting the night air. Rudolfo set that pace with long, deliberate strides, and when they were sufficiently away from the others, he slowed them. “Tell me,” he said.

Winters started at the beginning, updating him on Cervael’s death and the Mass of the Falling Moon, through Neb’s appearance and then disappearance with Isaak and the Watcher.

Rudolfo listened intently, his hands folded behind his back as he walked, and occasionally he interrupted to ask questions. When she reached the part about Jin Li Tam’s sister, he raised his eyebrows.

“A Tam in the Y’Zirite Blood Guard?”

“Yes,” Winters said. “Lady Tam said the woman told her to go with the regent when he asked.”

He nodded. “Continue.”

This is the part I dread telling him. She did not know why, but the thought of it knotted her stomach. Winters took a deep breath and continued. “Lady Tam also bid me tell you that she loves you and that you bear her grace above all others but your son. And that she would see him back to you.”

She saw him flinch at the words, and when he turned his eyes upon her, she saw anguish now mixing with his rage. “And you’ve known this ten days gone but did not send word of my wife and my son? Nor send word about my first captain?”

Winters looked away. “I did not, Lord.”

“Why?”

Look him in the eye. She forced her eyes toward his. “Aedric bid me not to. He knew you would try to pursue them. It’s in his letter.”

Now Rudolfo drew in a breath and slowly let it out. He turned away from her and toward Charles. “And tell me what you know about Isaak,” he said.

Charles looked at Winters, then back to Rudolfo. “I fear he is dead, Lord.”

Dead. Winters blinked back sudden, unexpected tears. This was what she’d feared, and hearing him say it aloud hollowed out a part of her.

“What leads you to believe that?” Rudolfo asked.

“I believe his sunstone overheated, Lord, during his fight with the Watcher. I think the earthquake was an explosion underground—a large one.”

How large, she wondered? Her mouth went dry, and Rudolfo asked before she could find the words.

“What about Neb and the Watcher?”

Yes. What of them? Charles glanced at her before answering, and she knew from the look on his face that she did not want to know what he was going to say.

He looked away from her. “I don’t see how they could have survived if they were nearby. Especially underground.”

No, Winters thought. Neb left the way he came. He went to do what needed doing. He went Home-Seeking. Isaak went with him. “But we can’t know for sure,” she said. “Neb was . . .” Her words trailed off as she thought about them. “He was different when we saw him. He came out of nowhere and he was stronger.” She shuddered at the memory of his choked voice, feeling the heat of his hands upon her body. Be whole. “He was faster.” She looked to Charles. “You saw it?”

“Some,” Charles said. “Mostly, we heard it. But she is right, Lord. Neb was holding his own against the Watcher.”

“That is curious.” Rudolfo stopped and stroked his beard. He looked at Winters. “You’re right. We cannot know for sure what’s become of them.”

But his eyes told her that he wasn’t hopeful. When he started walking again, he turned them back toward the scattered line of men, women and children who stamped their feet in the cold. “I will send scouts to your young officer with an offer of aid,” Rudolfo said. “I’ll have them gather what information they can.”

She blushed at the mention of Garyt ben Urlin, then willed the heat from her cheeks. “Thank you, Lord.” She paused, thinking she should say more but unsure of what that more should be.

They walked quietly, and when they reached the caravan, Rudolfo paused. “We have tents and food,” he said. “And when you reach Rachyle’s Rest, my new steward, Arturas, will help you find housing and work for your people.”

New steward? When she’d left with Lady Tam, Kember had been steward. And though she wanted to ask, she knew from the way he said the name that this was not the time. Instead, she inclined her head. “Thank you, Lord Rudolfo.”

He looked at Charles next. “And you have work waiting for you,” he told the man. “We’ve recovered an artifact from one of these Blood Scouts. We’re not sure what it does, but it’s been stored in the Rufello vault in your office.”

Charles bowed. “Yes, Lord. I’ll look at it.” He moved back into the line and recovered his pony from the woman who held its reins, but Winters stayed, still looking for the words.

Rudolfo spoke first, his voice so low that none could hear but her. “My disappointment is profound,” he said. “By withholding this information until now, you’ve robbed me of choices regarding my family . . . my son.” She forced her eyes to his and saw the anger and pain there.

“You are a queen, Winteria, and one who understands what it is to have your power and your choices taken away.” He paused and held her gaze. “I expected better of you.”

The heat on her face was different than earlier, and it arrived accompanied by a lump in her throat. She opened her mouth to answer him, but what could she say? She had wondered a hundred times whether or not she made the right decision. Before she could speak, Rudolfo climbed into the saddle and looked at the Gypsy Scout again. “I’ll have that letter now,” he said.

The man drew it from his sash and passed it up to his king. Lines of grief stood out on the scout’s face.

Rudolfo took it, tucked it into a pouch at his belt, and turned the horse. When he rode way, his back was straight.

Winters blinked tears of powerlessness and frustration. I did what was best for all of us. She knew when Aedric came to her that Jin Li Tam would’ve concurred as well.

Still, watching the result of that choice in the angry posture of the man who’d sheltered her, aided her since that dark night Hanric fell, Winteria bat Mardic felt a blade sharper than the Y’Zirite knives that had scarred her flesh.

This blade cut deep and cold.

Petronus

Petronus felt the heavy wooden crate crash against him, and he clung to the safety harness with white knuckles, trying to shout over the sound of shrieking metal and hissing air that filled the cargo bay.

The floating crate traveled the length of him, and he deflected it as best he could with his free arm. Across from him, he saw Rafe Merrique groping for purchase on one of his crew. Beads of blood floated on the air, bubbling out of a gash on the crewman’s head. All around the metal room, anything that wasn’t strapped down drifted. Grains of rice from a burst sack, beads of water from an open canteen. A medico kit moved past Petronus, and he snagged it then pushed it across the room toward the old pirate.

Rafe cursed and stretched out for it. “What in the hells is happening?”

“I don’t—” The weight of a mountain fell upon him before the words were out, and all around Petronus, everything that had hung suspended suddenly dropped as the ship bucked and shimmied.

The ship pitched starboard, and Petronus found himself pressed hard against the metal wall. As he rolled along with the vessel, the cargo bay filled with light and he saw a bright blue sky through a crystal porthole that slid by beneath him as he tumbled about.

He heard the sound of metal on metal and looked in the direction of the ladder that separated them from the pilothouse above and the engine room below. A mechoservitor moved down the ladder, steam rising from its exhaust grate. The metal man reached the deck, and another began its descent.

What are they doing? There were four of them now. The ship steadied, and the metal men moved across the deck quickly, pulling their way along the line of safety harnesses. The vessel shuddered, and the shrieking rose to a new and frenzied pitch. One of the mechoservitors staggered, steadied itself and moved quickly to Petronus.

“What’s happening?” he shouted as the mechoservitor lifted him to his feet.

“We’ve been attacked, Father Petronus. We are attempting to land.”

Attacked? He flinched when the metal man’s arm encircled his waist, but the sharp pain he felt in his left leg convinced him to accept the offered help. The mechanical man lifted him easily. Behind him, he saw Rafe Merrique and two others also being carried toward the ladder.

The ship pitched again, and he felt the gears grinding beneath his ear as the metal man staggered and then compensated.

When they reached the ladder, Petronus scrambled up it and into waiting metal hands that pulled him up and strapped him beside a still form. Neb.

He twisted in the harness to look at the boy but found the view beyond too compelling to resist. Two metal men worked the wheel while another sat in an odd contraption of levers and pedals. Just past them, through a wide crystal window, Petronus saw wisps of low-lying clouds shrouding a green carpet of jungle, interrupted occasionally by patches of blue water.

Something large and silver flashed by, and once again, the ship shuddered and then dropped suddenly. He heard a thud to his left but couldn’t turn to see what had happened. Rafe Merrique’s cursing was explanation enough.

“We are landing in the southern lunar sea,” the mechoservitor who worked the pedals and levers said, its voice booming in the confined space.

Petronus saw it now, rising up at them faster and faster as the ship continued its descent. He tried to force himself to watch, but in the end, he shut his eyes against it and held his breath.

When they hit the water, it knocked the wind out of him, and light exploded behind his closed eyes. His awareness shrank to a single point of focus—clutching at the harness against the tossing and bucking and shaking of the vessel. Everything else faded, and even the roaring around him was shut out.

He became nothing but fists hanging on until he felt a sharp pain in the back of his head and gave way to the gray that swallowed him.

When awareness returned, he once more found metal hands pulling at him. Watery light washed the cabin, and the air had changed. It was fresh and heavy with salt, nothing like the stale air he’d been breathing since they left the Named Lands, and all around him, he heard the rush of water.

The mechoservitor before him was dented. One of its eyes hung useless and dark, and the other guttered. It lifted him up, and Petronus felt other hands taking hold of him as he was passed along a chain of mechanicals and eventually laid out upon a twilight shore. He tried to roll over and found the light erupting behind his eyes again.

“I have you, Father.” It was Rafe.

The old pirate carefully turned him over, and the first thing he saw was the massive brown-and-blue world that filled the sky and painted the landscape with an ethereal twilight.

Petronus lay still and blinked until the familiarity of that vast world registered. He could see the two mountain ranges he’d grown up with— the Dragon’s Spine marching across the northern reaches of the continent and the Keeper’s Wall running north to south, carving the Named Lands off from the desolation of the Churning Wastes.

“Gods,” he whispered. “I’m on the moon.”

“Aye, Father,” Rafe said.

Petronus took his eyes off the sky and looked to the pirate. “Whathappened?”

“I know what you know. We were attacked and crashed in the sea.”

Petronus forced himself to sit up, threads of light spider-webbing his field of vision as he did. Shaking it off, he looked around. They were on a strip of beach, and to the right, a mechoservitor bent over a still form.

“Neb?” The boy didn’t move, and Petronus felt fear rising in his stomach. He tried to stand and Rafe steadied him.

“The boy’s asleep, Father. He slept through it all.”

Asleep? He’d not seen Neb since the day they loaded him into the vessel, naked, burned and unconscious. But the boy had spoken into his mind, and his words were full of despair. We’ve failed. Isaak is dead. The dream is lost. The staff is lost.

And now, Petronus thought, this. He limped to Neb and crouched. The metal man looked up briefly, its eye shutters flashing open and closed, then returned to checking the boy. From what the old man saw, there were no obvious injuries. The hair was growing in where it had been burned away, and the boy’s left hand and arm were covered in the pink of new skin. Anyone else would’ve died from the shock of the burns he’d sustained, but Petronus knew now that Neb wasn’t anyone else.

He’d heard that voice, as well, dropping into his mind, commanding him to fall back and accompany Neb. It was a voice that started his nose to bleeding and his head to pounding.

It was the voice of the Younger God, Whym, declaring himself Neb’s father and with that pronouncement challenging everything Petronus had ever believed.

He reached a hand out to touch the boy’s cheek. It was warm. “Neb?”

The mechoservitor looked up again. “Lord Whym continues to regenerate.”

Lord Whym. When he’d met Neb, the boy was nearly mad from the loss in Windwir’s pyre. Petronus had watched him rise to the challenge of leadership in the grave-digging camp. He’d never imagined this. “Is he okay?”

Billows wheezed. “He is functional,” the metal man said.

Petronus nodded and looked back to the water. Rising up from it, half buried, lay the massive hulk of the ship that had carried them here. Five metal figures formed a line, passing what could be salvaged out of the ship and onto the sand. The others—two scouts and a sailor— gathered around two forms now covered with wool blankets.

We’ve dead to bury. And one of them was his friend, Grymlis, killed by kin-wolves as they raced to board the ship. Petronus felt the grief of that loss. It was a fog that hemmed him in, and not even the wonder and fear of being shipwrecked on the moon could lift it.

What now? He stood and went to stand with the others. They looked to him, their bruised faces pale and expectant in the light of the world that hung above them.

As a boy, he’d spent hour upon hour playing out the apocryphal One Hundredth Tale of Felip Carnelyin, he and his boyhood playmates turning the backwoods of Caldus Bay into a vast lunar jungle filled with new smells, new sights and dangerous beasts. And now, he stood upon the shore with that jungle stretching out behind him, smelling salt, ozone and the sweet scent of flowers he did not recognize on the midnight air. This wasn’t how he imagined landing upon the moon, back when he was young and playing out Carnelyin’s adventures.

Still, for now they were alive and safe enough, though he wondered what manner of mechanical or magick could bring down a vessel such as theirs. And more importantly, he wondered if it might return for them.

Regardless, he realized, there was work that must be done, though it grieved him that it was their first work in this new place.

He looked down at the bodies of those they’d lost and then turned to the growing pile of boxes, crates and barrels. He walked to it, and dug around until he found a shovel still wet from the sea.

“We’ll need white stones,” he said.

And then, once more, Petronus set about the task of burying his dead.

Requiem © Ken Scholes 2013